Jacob Kainen was the son of Russian immigrants. His father was a tool-and-die maker, an inventor, and an occasional sculptor. His mother had a great appreciation for music, art, and literature. Both parents encouraged their children in their artistic and academic pursuits.

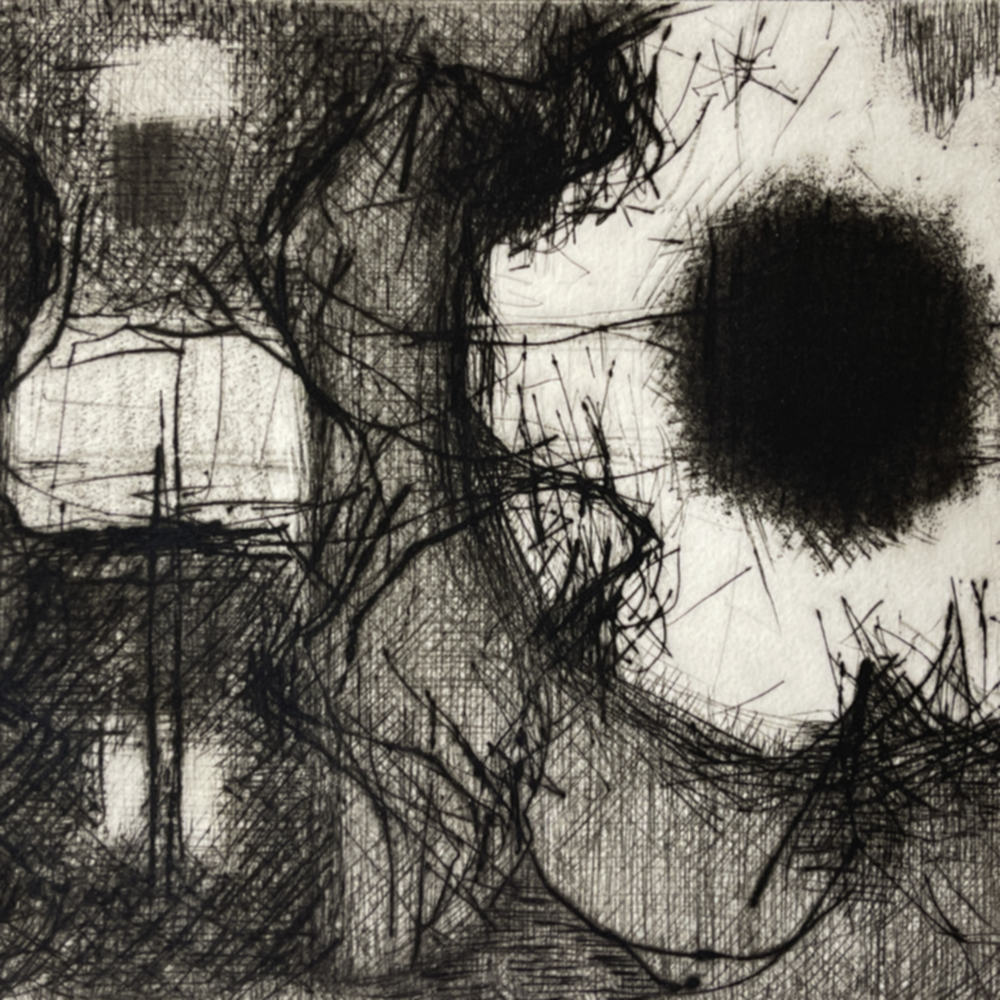

When the family moved to the Bronx in 1918, Kainen’s budding passion for art and literature was fueled by trips to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Public Library. He graduated from DeWitt Clinton High School at age sixteen and then took drawing classes at the Art Students League. It was during this time that Kainen made his first prints by pulling drypoints on zinc plates through the ringer of his mother’s washing machine.

Kainen was admitted to the Pratt Art Institute in 1927. After several years, Kainen soured on Pratt, believing that he had surpassed his peers and even some teachers and viewing Pratt’s curriculum backward, anti-modernist, and rigid. In his final year, the fine arts curriculum was revamped as a commercial art program; Kainen was outraged. He refused to take commercial courses and set up his own class—and was expelled three weeks before graduation. (He would finally receive his diploma from Pratt twelve years later.)

Kainen’s expulsion from Pratt proved pivotal. He sought out other avant-garde artists in the city, especially those who shared his institutional contempt, and frequented cafeterias where urban artists met to debate and develop ideas—social and aesthetic. He began to engage with the emotive palette and gestures of German expressionism and the social awareness and ferocity of Social Realism during the 1930s. He joined the Artists’ Union and became a contributor to its journal, Art Front. (He would later become its editor.) He was also an occasional cartoonist and reviewer for The Daily Worker.

From 1935 to 1942, Kainen worked for the Graphic Arts Division of the Works Progress Administration. He was able to learn lithography, etching, woodcut, silkscreen, and other media as part of this project while devoting his personal time to painting. He soon found, though, a deep love of printmaking and he was able to bring his painting skills to bear on printmaking media.

During the late 1930s, Kainen and seven other painters formed the “New York Group”, an exhibiting body that Kainen wrote “is interested in those aspects of contemporary life which reflect the deepest feelings of the people; their poverty, their surroundings, their desire for peace, their fight for life.”

In 1942, Kainen moved to Washington, D.C. He hated leaving New York, his friends, and fellow artists, but he was increasingly worried about the inconsistent work for which the WPA was famous. He took a job as an aide in the Division of Graphic Arts at what is now the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Kainen thought that his move to Washington would be temporary. He was, of course, entirely incorrect. Upon arriving in Washington, Kainen was immediately shocked by its rudimentary and slow-paced art scene. Washington was then a wasteland for contemporary art. Kainen would spend the rest of his life in Washington and would be a major force in turning that around. Kainen became an assistant curator and then a curator at the Smithsonian, and over that time he brought about massive change. He completely reshaped the Division of Graphic Arts, he built the graphic arts collection. His print exhibitions brought the work of Stanley W. Hayter, Josef Albers, and many other luminaries to Washington audiences. Kainen was central to—perhaps the very center of—creating the postwar Washington art scene.

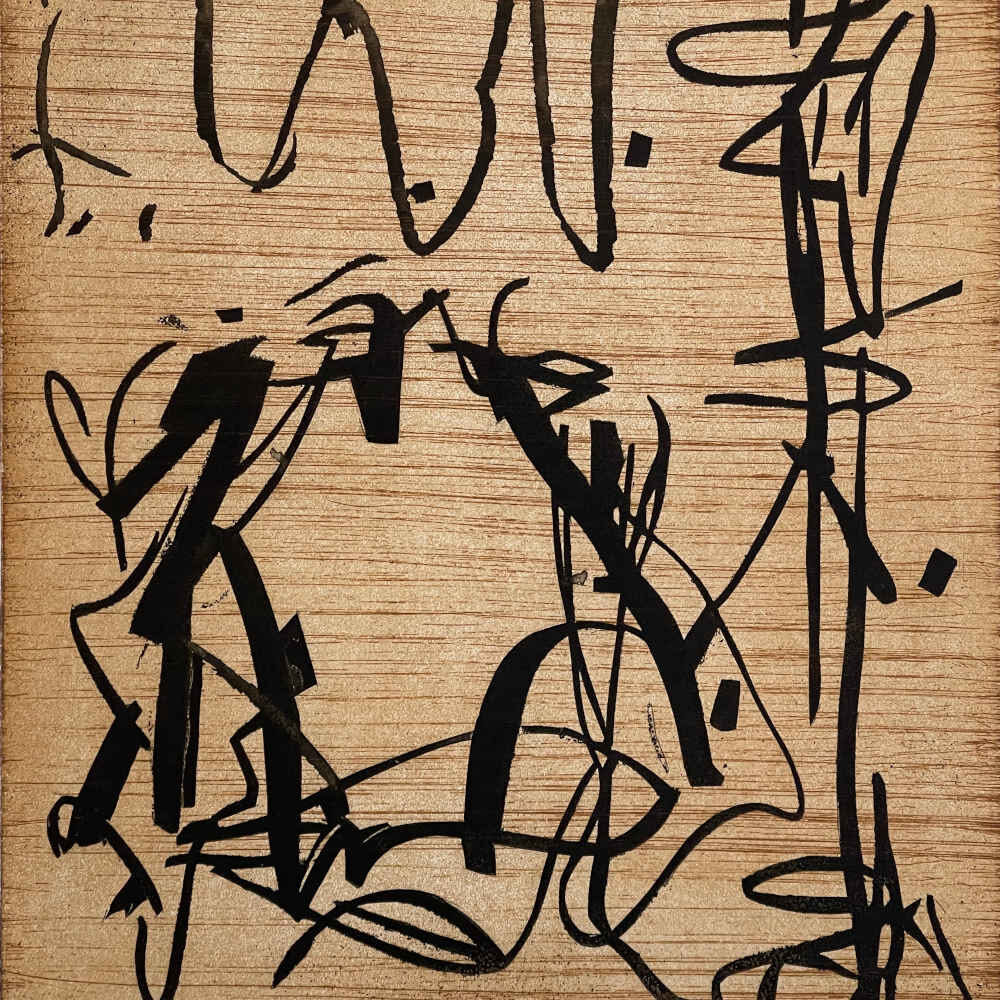

Kainen’s own paintings from the 1940s show a marked shift away from Social Realism toward abstract expressionism. He found inspiration in the Victorian skyline and architecture of the buildings surrounding his studio in Dupont Circle. He was one of the first abstract artists working in the city, and he produced abstract compositions of symbols and forms that resounded with both his physical surroundings and personal experiences.

In 1946, Kainen was included on Ad Reinhardt’s “Tree of Modern American Art,” a succinct map of the artists and movements defining art of the modern era. In 1947, the Washington Workshop Center for the Arts opened its art school, and Kainen served as a painting and printmaking teacher. He helped to make the workshop a magnet for new talent and was a guide to many important artists. He was instrumental in furthering the careers of artists such as Gene Davis, Morris Louis, and Alma Thomas.

In 1949, Kainen’s loyalty to America was challenged by the Civil Service Commission’s loyalty board because of petitions he had signed and articles he had written for leftist causes as a young man in New York. Congress pressured government agencies to fire “disloyal” employees, but Kainen kept his job not only because of the attitude of Smithsonian managers but also because J. Edgar Hoover had once sent Kainen a letter saying, “You’ve done our country a great service” after Kainen had taught printing methods to FBI trainees. The strain of this period was evident in his vivid abstractions, with titles like Exorcist (1952) and Unmoored #2 (1952). (Kainen was finally cleared of formal charges in 1954.)

In 1949, the Corcoran Gallery of Art held a retrospective of Kainen’s prints. In 1959, Kenneth Noland organized a retrospective of Kainen’s work at Catholic University. Kainen later described that show as one of the most important of his career.

By 1966, tiring of his dual careers as an artist and curator, Kainen attempted to retire from the Smithsonian, but David Scott, the museum director, persuaded him to become a part-time curator of prints and drawings. By the time he finally retired in 1970, Kainen had increased the collection from 1,000 to 7,000 works. Kainen continued to serve as a special consultant to the museum for nineteen years. In 1971-1972, Kainen taught painting and the history of printmaking at the University of Maryland. Kainen was also a scholar, whose works included the acclaimed monograph John Baptist Jackson: 18th-Century Master of the Color Woodcut and the book The Etchings of Canaletto.

After his retirement from the Smithsonian, Kainen’s work shifted back to pure abstraction, yet this body of work contrasted dramatically with his abstraction from the early 1950s. These paintings no longer reflected the stress of persecution, but rather conveyed the tranquility he found later in life.

Between 1970 and 1980, Kainen had at least one show each year, including an exhibition at the Pratt Manhattan Center in 1972, two shows at the Phillips Collection, and two shows at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. A major 100-piece, 60-year retrospective of Kainen’s paintings was held in 1993 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. His biography can be found in most major surveys of important artists, including the 1980 history American Prints and Printmakers by influential scholar Una E. Johnson.