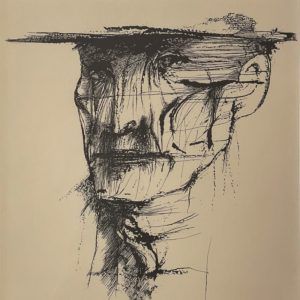

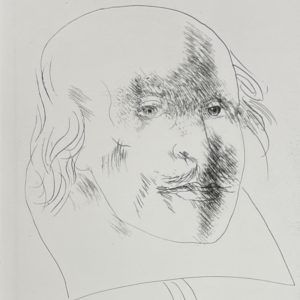

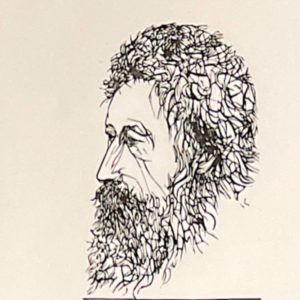

Leonard Baskin’s great skill was his ability to depict in an abstract style man and his relation to the world. He often viewed humanity with bleakness and dismay. He saw humans as often heroic but always flawed and he saw the human condition—at least, in the Twentieth Century—as marked by spiritual death, decay, and vulnerability. Baskin’s Judaism was central to his work and his world view. It is, perhaps, unsurprising that he viewed the world with such bleakness, having been a young man during World War II. Over time, his attitude toward the nature of man grew more generalized, but no less moralistic or didactic.

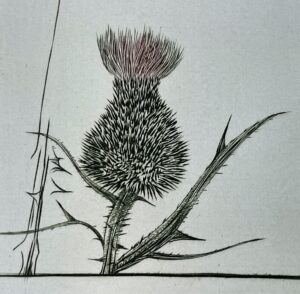

Baskin’s world view is evident in his highly expressive works on paper and his inventive woodcut technique.

Importantly, Baskin felt alone in his view that art was meant first and foremost to be expressive, to be critical, to speak loudly. He disdained the abstractionism which was rapidly occupying the attention of the art world; he sharply disputed the abstractionists’ opinion that a thing of beauty could be art even without having an underlying message.

Like Karel Appel, Baskin knew at a very early age that he was to be an artist. He began studying at the age of 15 with the sculptor Maurice Glickman at the Educational Alliance in New York City. After service in the Navy during World War II, Baskin earned an undergraduate degree from the New School for Social Research (take a look at Youngerman’s design celebrating the New School’s 50th Anniversary). He then studied at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere in Paris and at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence before returning to the U.S. He also studied at the Yale University School of Fine Arts. While at Yale, he founded one of America’s first and finest fine art presses, the Gehenna Press.

Like so many other great artists, Baskin was a teacher, teaching printmaking and sculpture at Smith College and Hampshire College.

Baskin’s work can be found at the Hirshhorn, the Art Institute of Chicago, MOMA, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the National Gallery of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Vatican Museum, the Library of Congress, the Israel Museum, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, among many, many others. He created numerous large-scale works of public art including the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, DC, and the Holocaust Memorial in Ann Arbor.

Baskin is one of the Twentieth Century’s most celebrated artists. Among many other honors, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1963 and was awarded the Academy’s Gold Medal in 1969. In 1989, he was awarded the Gold Medal by the National Academy of Design.